Shostakovich: artist under a repressive regime

20 December 2023, article, text: Luc den Bakker

Amare’s Concertzaal will soon resound to the music of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony and Eighth String Quartet. He was a composer who, despite all the misery, never lost his humanity, and whose work remains powerfully evocative until today. How best to listen to this monumental and yet highly intense music? We offer some guidelines below.

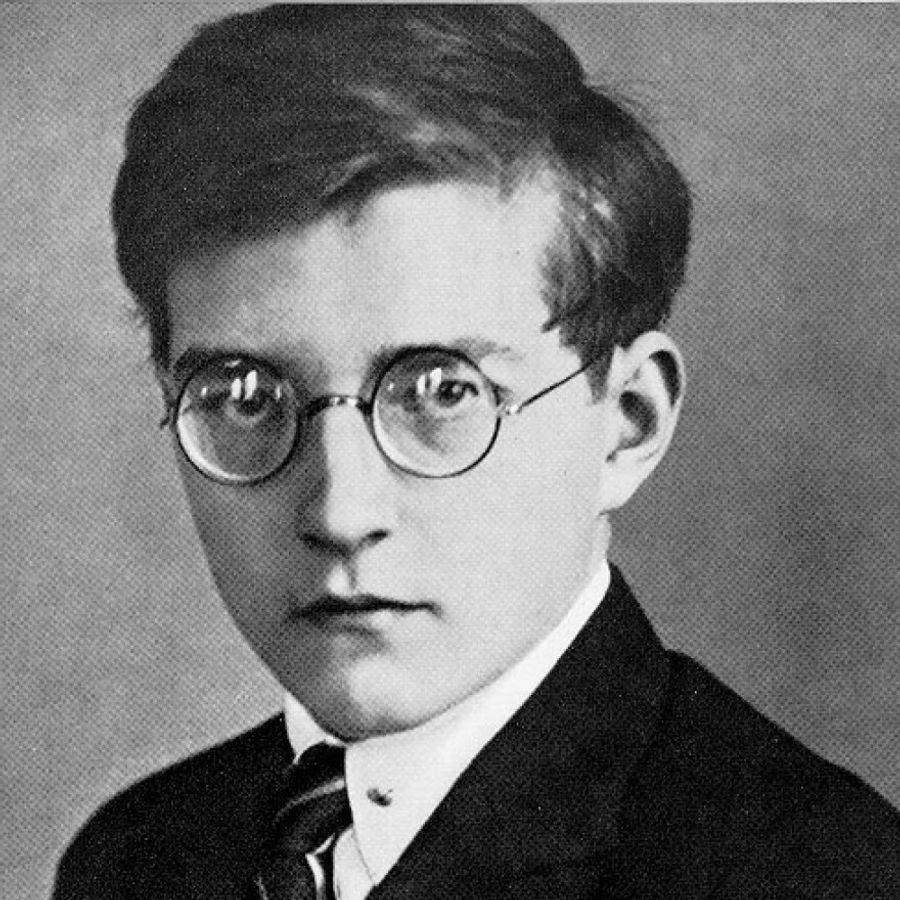

Before discussing the music, let’s first look at the life of this great Soviet composer. For we cannot talk about Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) without looking at the political situation in the Soviet Union at the time of his life. Shostakovich lived through the worst years, from the chaos directly following the Russian Revolution to Stalin’s reign of terror, and the German invasion and siege of Leningrad. His life and music are inextricably tied up with this dark and turbulent history.

Shostakovich's life

Shostakovich was born in 1906 in a city then still known as Petrograd, in what was then still Czarist Russia. He displayed an exceptional talent for the piano at a young age, and also started composing early in life. He was admitted to the Petrograd conservatoire at the age of thirteen, in the year 1919; just two years after the revolution that drastically changed the country.

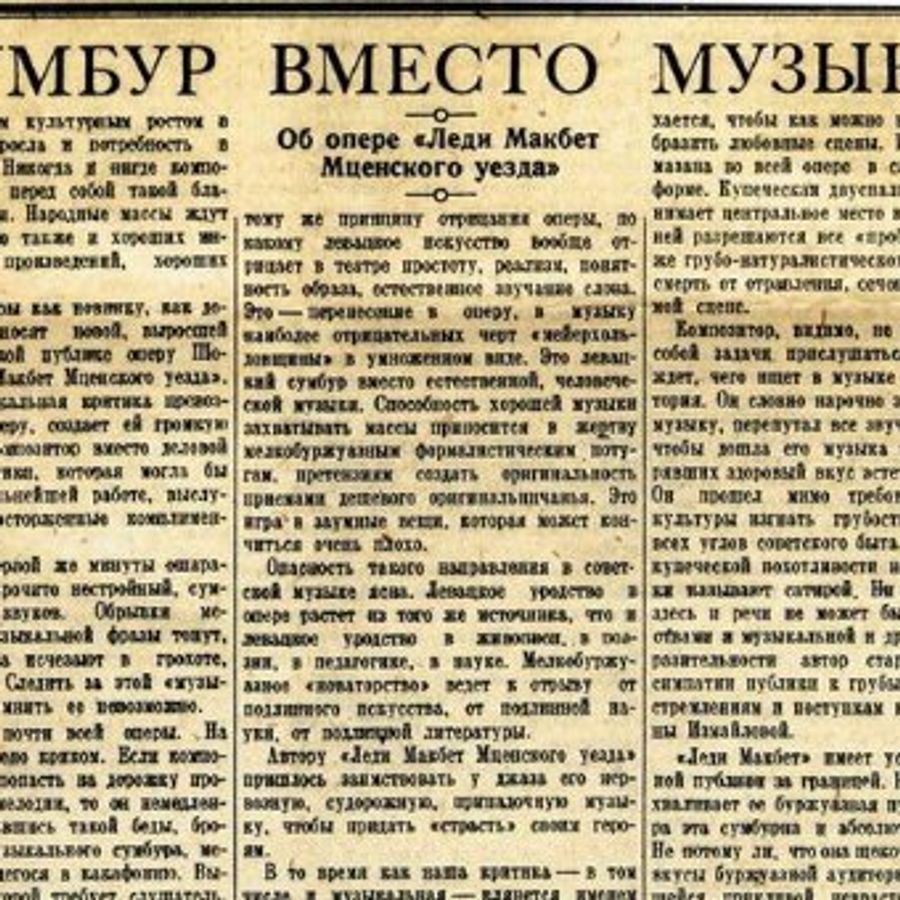

Shostakovich’s first conflict with the authorities followed one of his first great successes. His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District (1934), about a married woman who develops an affair with a young man and is eventually driven to commit murder, was highly popular at first. But Stalin’s terror in those years was particularly aimed at artists, and as a prominent composer, Shostakovich was an obvious target. A devastating review was published in the Pravda newspaper, the mouthpiece of the Communist Party, and this marked the start of a lifelong tension between Shostakovich and the authorities.

A memorable composition from the war years is the Seventh Symphony, Leningrad (1941), dedicated to the city under siege. Shostakovich had wanted to join the fight against the German army, but his poor eyesight made him unfit for military duty. Later, as a prominent resident, he and his family were evacuated. In the midst of war, in a cold and hungry and largely destroyed city, the symphony was performed by brave musicians for a deeply touched audience.

Perhaps on account of their common enemy, relations between Shostakovich and the Communist Party improved during the war years. This was soon to change again, however, as a second wave of terror took hold. Along with a number of other composers, Shostakovich was reproached for creating music that was insufficiently proletarian and too ‘formalistic’ – meaning something like ‘too abstract’. He was no longer sure of his life, and an anxious and distrustful mood spread among his colleagues as well.

Life became easier after Stalin’s death in 1953. Shostakovich was given more artistic freedom, although still subject to constraints. He joined the Communist Party in 1960; a move that allowed him to assume important positions in the music world and to receive honorary distinctions. It was part of the Communist Party’s attempt to foster closer relations with the intellectual elite. We will probably never know for sure whether Shostakovich participated voluntarily or under coercion.

Throughout the years he continued to compose with a passion, in his characteristic late-Romantic style, sometimes sombre and bitter, at other times light and full of absurdist humour. He died of lung cancer in 1975.

Listening along two lines

We can distinguish two lines in Shostakovich’s music, which together offer a good picture of what it meant to be a human and artist under a repressive regime. The first consists of his fifteen overwhelming symphonies, including the Fifth. This series is evocative of the Soviet Union’s turbulent history.

The second line consists of the fifteen intimate string quartets, including the Eight. The string quartets offer a glimpse of the internal turmoil that Shostakovich experienced during his life. You can listen to each of these lines in a different manner.

The Fifth Symphony: a sincere or insincere confession?

Shostakovich composed his Fifth Symphony (1937) during the period that he was severely criticised for his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District, as described above. One of the reproaches was that he had not composed the music in an accessible, optimistic and heroic style, referred to as the social-realist style. And in the Soviet Union, it was dangerous to not be on a good footing with the authorities. Shostakovich’s life was at risk.

It was in this context that he composed his Fifth Symphony. The symphony carried the subtitle: ‘A Soviet artist’s response to justified criticism’. It is a sentence reminiscent of the ‘confessions’ that prisoners would offer at the end of show trials. The symphony is of a more conventional form and musical language than Shostakovich’s earlier works, and it contains some triumphant melodies. The authorities were pleased.

But was the ‘confession’ sincere? The Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov published a book in 1979 titled Testimony. According to Volkov, the book contains Shostakovich’s memoires as dictated to him. In the book, Shostakovich offers the following explanation for the seemingly optimistic sound of the symphony: "It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’" And indeed, it doesn’t take much effort to discern a wry undertone in the exuberant music.

Volkov’s book stirred up a lot of controversy, however. Ever since its publication, strong doubts have been voiced about its authenticity. Critics suspect that Volkov fabricated the texts to create an image of Shostakovich as a determined dissident. And even if the authenticity of the material could be verified, its significance is questionable. It cannot be ruled out that Shostakovich’s ideas about his Fifth Symphony were very different in the early 1970s than in 1937, when he composed it. The image of Shostakovich as a dissident who incorporated codified criticism of the Soviet Union in his work has become very popular. But whether it’s true or not is a matter of debate.

Fortunately, music is an abstract medium and very flexible. If you want to listen to the symphony as a highlight of the social-realist style, then that’s perfectly possible. If you prefer to pick out a subversive, pessimistic undertone, then that’s fine too. It’s up to you.

The Eighth String Quartet: (bare) comfort?

The string quartet is probably the most popular genre in classical music for composers to express their most intimate feelings. Consider for instance Beethoven’s famous late quartets, or Schubert’s quartets. The same applies for the fifteen string quartets that Shostakovich composed. Together they offer a biographical overview of his life: he composed his first string quartet in 1930, while still in his early thirties, and the last premiered in 1974, one year before his death.

Of all his string quartets, the Eighth String Quartet, to be performed in Amare, is one of the best known. This work was composed during the relatively mild Khrushchev years, when Shostakovich was less compelled to hide his true nature. A notable feature is his use of the notes D, Es, C and B – or, according to German custom, D, Es, C, H: Dmitri SCHostakovich. In this way he literally wrote himself into the music.

In 2022 Amare hosted the internationally renowned Quator Danel quartet, to perform the entire series of Shostakovich's string quartets over the course of five concerts. At the time, violinist Marc Danel remarked: “In general, Shostakovich, like Beethoven, is somebody who tells a story. It’s very, very actual at the moment. But I remember that one our teachers said: if everyone would have understood the message of Beethoven, war would be impossible. I mean, Shostakovich is really taking you somewhere and bringing you somewhere, and it’s very much about humanity. I think these pieces make you more human. It’s going through a lot of suffering but it’s never without hope. […] The main reason why we play Shostakovich is just because it is one of the greatest cycles ever written for string quartet.”

At a time when human lives are being sacrificed by ruthless rulers, Shostakovich's music sounds as relevant as it did on the day of the premiere. And perhaps we will find some comfort in his notes, which so urgently give a voice to the oppressed.

Shostakovich in Amare

-

Past eventFri 8 Nov ’2420:15 - 22:15