What is the St Matthew Passion?

Last update: March 2025, article, text: Luc den Bakker

Even if classical music is not your cup of tea, you’ve likely heard of the annual performance of the St Matthew Passion around Easter. Here, we explain a few things about the story and share listening tips for both novices and veterans.

Easter is the time of the St Matthew Passion, which tells the story of Christ’s final days, usually in the form of J.S. Bach’s famous composition. The Netherlands has a rich tradition of St Matthew Passion performances: everyone wants to be and be seen in Naarden’s Grote Kerk (Great Church), and amateur choirs throughout the country eagerly look forward to the passion days.

It is a national love affair that seems insatiable. Again and again, the story of the Passion is told and retold in various ways, and not just for Christian believers. People of all faiths and beliefs are enthralled by the tale’s evocative power.

In fact, you may have heard so much about the St Matthew Passion that you’ve started considering attending a performance. Or perhaps you’ve been a loyal visitor for many years, and would like to know more about the story behind it. What exactly do you hear? What can you listen out for? How can you get the most out of this musical experience? Read this article for tips and recommendations!

What is a Passion?

Briefly put: a Passion tells the story of Christ’s death. It begins with Judas’s betrayal and leads the listener through the well-known scenes of the Last Supper, the Mount of Olives and the crowing rooster. The story ends with Christ’s death on Good Friday. A Passion telling does not include the Resurrection.

Bach was certainly not the first composer to put this narrative to music: Passion concerts have a long history. Much of the form’s development occurred in Lutheran Northern Germany, as the Lutheran faith considers it important for everyone to know the Biblical stories. No Latin, no complicated compositions with so many competing voices that they are impossible to make heads or tails of: instead, everything should be in the national language, so that everyone can understand it. The composer’s role is to bring the story to life for all believers, through music.

You can still notice this approach. Hence listening tip No.1: bring along a printout of the original text and a translation in your own language. With the text in hand, it is fairly easy to follow what is happening in the story, and that makes the listening experience so much richer. After all, that is what the composition was intended for.

What am I going to see and hear?

A Passion is an oratorio, a kind of audio play set to music from beginning to end. Different vocalists perform the various roles in the story – in this case, Jesus, Peter, Judas, Pilate, and so on. When you hear a choir singing, they represent the people or, at other times, the disciples.

A special role is reserved for the Evangelist, who does not feature in the story itself, but narrates what is happening for the audience. “Jesus and his disciples arrived at the Mount of Olives,” “Pilate washed his hands”, and other statements in that vein.

This is what distinguishes an oratorio from an opera. The singers do each play a part, but they are not dressed in costume, they do not act out their roles, there is no stage décor. Everything is conveyed purely through text and music, and that is the power of this art form: it is not a spectacle, but a meditative experience, an opportunity for introspection.

Listening tip No. 2: during the performance, close your eyes every now and then. After all, the story is not taking place in front of you, but inside your mind.

How is the music structured?

In terms of structure, a Passion consists of three alternating components: recitations, arias and chorales. Once you know what to listen out for, they are easy to tell apart, which helps keep track of the whole.

Each of the components serves a specific function:

- Recitations drive the story forward. The melodies in recitations are often fairly monotonous, the instrumental accompaniment minimal. The speaker is usually the Evangelist, who literally recites a Biblical passage and explains – in clear, simple terms – what is happening in the story;

- Arias, on the other hand, are the story’s pause button. One or several soloists sing a beautiful, intricate melody accompanied by a rich instrumental score. Rather than being quoted from the Bible, the text was usually written by a contemporary of the composer. It is an interpretation of the story, and often contains a great deal of repetition that produces an almost meditative effect. The audience is invited to take a moment to appreciate the emotional charge of the story’s events;

- Chorales are solemn, stately melodies sung by the choir. They do not represent the perspective of a character within the story; instead, they represent us, the viewers. Stepping back from the arias and the overwhelming emotions of the narrative, the chorales contemplate the deeper truths contained within the story.

Each of these three components fulfils a crucial role within the whole: it is their alternating diversity that makes the musical experience what it is. And once you are able to recognise the differences between the recitations, arias and chorales, you understand what the music wants from you at any given moment.

Don’t let the purists hear this, but: if you want to warm up your ears in advance, there is no shame in a bit of selective listening. Listening tip No.3: pick a few highlights from the St Matthew Passion, your favourite arias and chorales, and listen to them over and over (or use a selection created by someone else). The more familiar the goosebump moments are, the more touching they become. The larger narrative can wait until the live performance.

The musical style

The previous section, we hope, has already helped you make some headway towards an optimum St Matthew Passion live experience. But as you might expect, we have barely scratched the surface – so if you want to dive even deeper, read on to find out about the Passion’s musical style.

Johann Sebastian Bach was a composer who lived from 1685 to 1750. The musical style of his age was known as Baroque, and it is therefore very likely that, when you take your seat in the concert hall, you will see a Baroque orchestra on the stage. (This doesn’t have to be the case – people have come up with all manner of exciting arrangements, but here we shall assume so, for the sake of simplicity).

So: a Baroque orchestra. If you have any experience with symphonic orchestras, you will immediately notice a few differences. To begin with, Baroque orchestras are a lot smaller, and many of the instruments look slightly different – or even nothing like what you are used to at all. Lutes, viola da gambas, harpsichord… and even the instruments that look familiar, like the violins, are actually different: they have sheep gut strings, and light, curved bows. Believe us when we say that this completely changes the sound! For those who are interested, this YouTube channel introduces various Baroque instruments.

The Baroque era also favoured a different style of composition than today’s listeners might be used to. The music does not try to overwhelm, it does not pick you up and sweep you away without a moment’s thought for your feelings on the matter. Instead it presents you with beautiful melodies, unexpected harmonies, clever musical constructions – what you choose to do with them is up to you.

Listening tip No. 4 might be somewhat easier said than done, but it’s still worth trying: make sure that you’re relaxed while you’re in the concert hall. With a clear mind, the experience is that much more beautiful. How can you do that? Well, try not to drink a gallon of espresso ahead of the concert, don’t schedule a scary dentist’s appointment afterwards, that sort of thing. If at all possible, of course.

Why “St Matthew”?

All right, the “Passion” part is clear enough now, but what about the “St Matthew”? Why is that name part of the title?

The life of Jesus Christ is told four times in the Bible. Those four versions, known as the gospels, are attributed to four different authors: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Although the stories largely line up, there are a few interesting differences, such as in their descriptions of Christ’s crucifixion.

For example, in the Passion as told by Mark – the oldest and shortest of the four gospels – Jesus says very little. At the end, he cries out in despair: “My God, why have you forsaken me?”. The focus of this gospel is on Jesus’s humanity and his suffering. In Luke, on the other hand, it seems as if Jesus is completely in control of the proceedings. “I assure you, today you will be with me in paradise,” he says to the crucified thief next to him, and then, fully at peace: “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

Bach chose to put music to Matthew’s version. Why Matthew? Well, compared to Mark and Luke, Matthew takes the middle road. As in Mark’s gospel, human suffering is a central theme, with Jesus crying out the same sorrowful words: “My God, why have you forsaken me?”. However, the text also follows Luke’s suggestion that, being the son of God, Jesus knows what he is doing. Choosing this gospel allowed Bach to place Christ’s suffering centre stage while also devoting attention to the deeper reasons behind it.

What about John, then, the last gospel to be written and the most divergent of the four? Actually, Bach wrote music for this gospel too, and it is another heart-wrenchingly beautiful composition. Listening to Matthew’s and John’s Passions side by side is a very special experience: you can clearly hear how the esoteric, philosophical John leads to completely different music than the biographical, human Matthew.

If this all sound rather too religious for your liking, don’t worry: a performance of the St Matthew Passion is anything but a church service. A large part of the audience is a hundred per cent secular. The power of this composition simply speaks to people, regardless of faith or belief.

The history of the Passion genre

Bach did not come up with the concept of the Passion: his composition is part of a long, rich tradition that primarily flourished in Lutheran, German-speaking regions. Amare likes to do justice to the full scope of this genre, and regularly schedules performances of other Passions: Heinrich Rolle’s and Johann Sebastiani’s, for example. To write these compositions off as just “precursors to you-know-which-one” is to do them injustice: they are phenomenal works in their own right.

That leads us to listening tip No. 5: Try attending a passion by a different composer than Bach for a change. The story has countless layers, and every interpretation offers something new to discover!

After Bach’s death, his works fell into obscurity, including his St Matthew Passion. Until the early nineteenth century, that is, when composer Felix Mendelssohn rediscovered the piece and championed many performances. He did rearrange the piece extensively to satisfy the musical fashion of his day, something that we prefer not to do now, but it must be said that the St Matthew Passion owes much of its present popularity to Mendelssohn’s efforts.

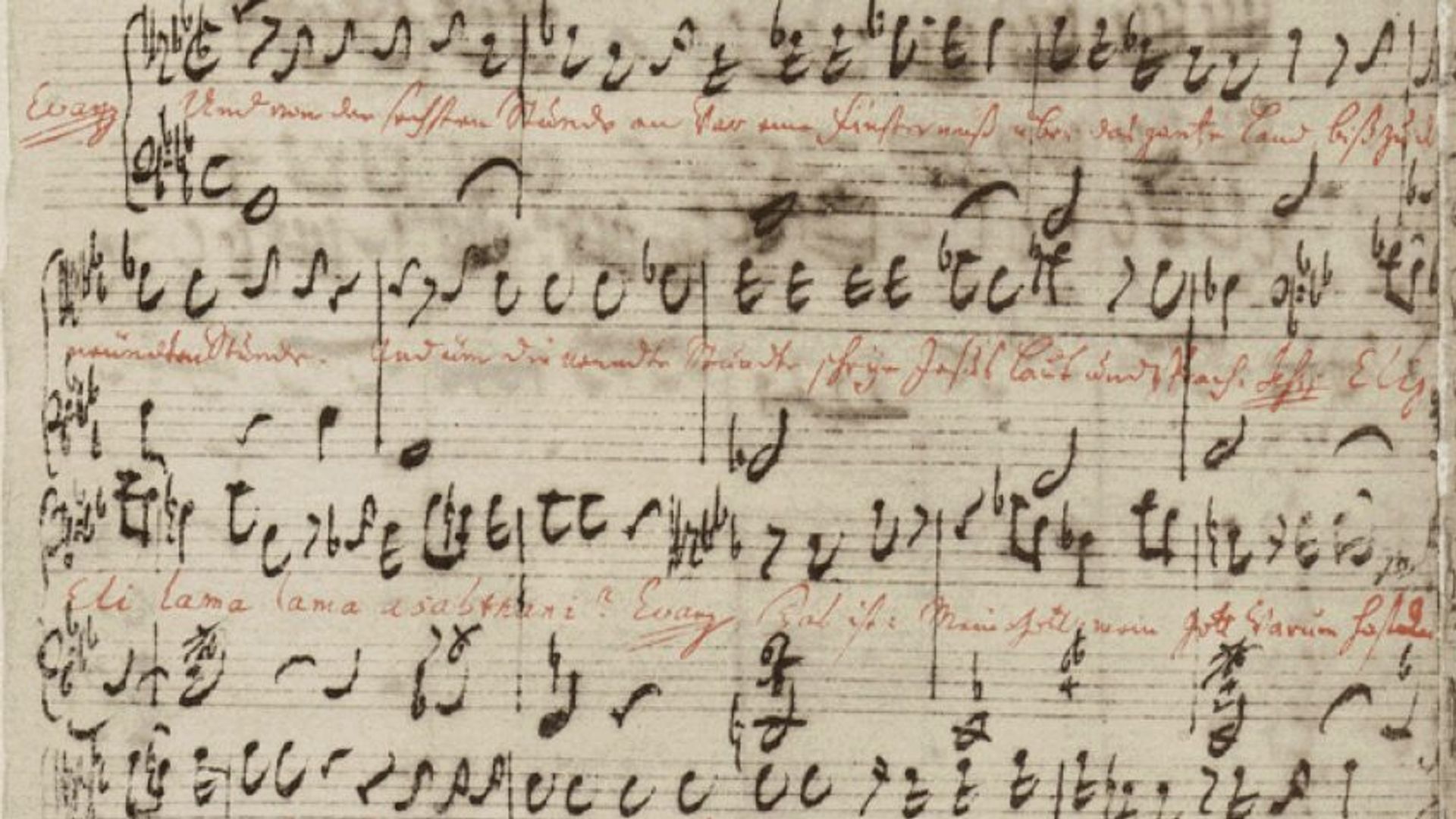

The twentieth century saw the emergence of a new musical movement: historically informed performance. This movement called for music to be performed as it would have sounded in the composer’s day. Old instruments were recreated, and musicologists studied original manuscripts. In response to the Romantic versions of the St Matthew Passion, a tradition of authentic performances by the Netherlands Bach Society in Naarden’s Grote Kerk (Great Church) born. These annual performances are still considered the leading example of their kind.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Passion as a genre fell out of favour among musicians, although – remarkably enough – it saw a resurgence in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1966, Penderecki (Poland) wrote his St Luke Passion, Pärt (Estonia) composed Passio in 1982 and MacMillan (Scotland) penned his St John Passion in 2007, to name just a few. In 2000, the Internationale Bachakademie Stuttgart commemorated the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death in a very special way: by commissioning the composition of four new Passions, one for each gospel. The chosen composers together broadly reflected contemporary classical music. The German Wolfgang Rihm – who once considered priesthood but has since become agnostic – wrote the neoromantic Passus Deus to Luke’s gospel; the Jewish Argentinian Osvaldo Golijov infused his La Pasión según San Marcos with Latin-American and Jewish folk music. Tan Dun, originally from China, combined the Christian narrative with Buddhist ideas in his Water Passion after St. Matthew, and Sofia Gubaidulina, raised in the Russian Orthodox tradition (which places great importance on Easter), appended her St John Passion with a St John Easter – in other words, the Resurrection. Thus the Passion has truly become a global phenomenon.

In fact, that phenomenon has even broken through the bounds of the genre: in the 70s, Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber wrote a popular rock opera about the crucifixion. Based on all four gospels at once, this Passion is remarkable for the central roles it awards to Judas and Mary Magdalene. We are talking, of course, about Jesus Christ Superstar. And we should also mention The Passion, the popular annual Dutch television programme produced by the EO and KRO-NCRV media companies.

Even with the secularisation of modern society – or perhaps because of it – people clearly remain inspired to continue telling and retelling the story, in old ways and new.